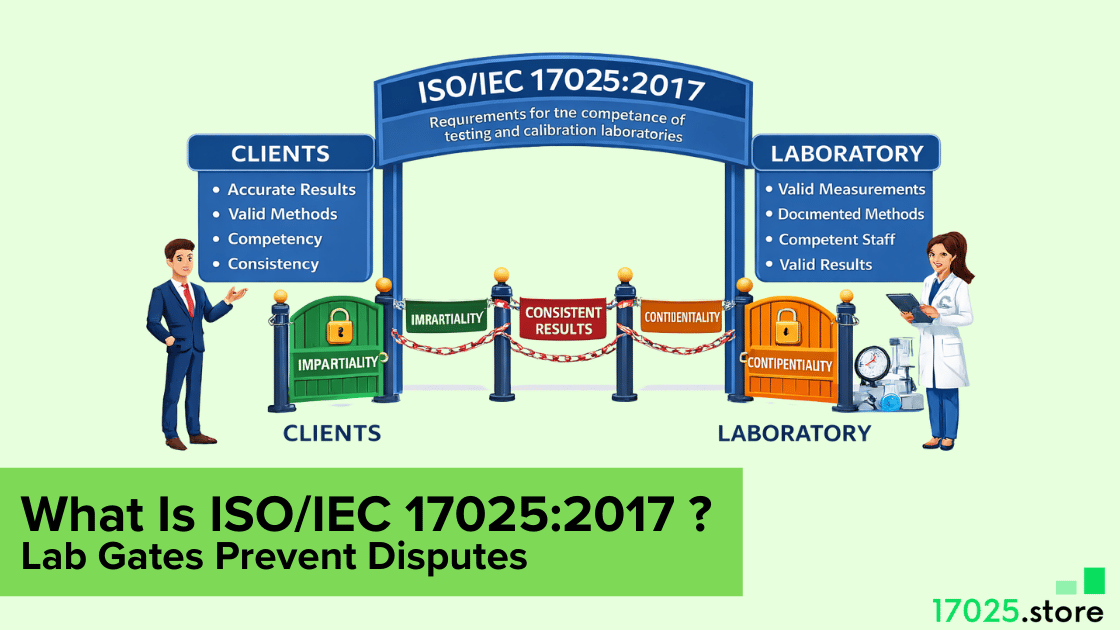

An ISO 17025 internal audit is your lab’s planned, recorded check that your system and technical work produce valid results. This playbook demonstrates how to develop a risk-based audit program, conduct a comprehensive audit of a real report from end to end, write defensible findings, and close corrective actions with supporting evidence. Use it to prevent repeat nonconformities and protect traceability.

Most labs fail internal audits for one reason. They audit paperwork, not the measurement system. A strong internal audit proves the result pipeline is controlled, from contract review to report release. That focus reduces customer complaints, reduces rework, and stops “we passed the audit” from masking weak technical control.

What ISO 17025 Internal Audit Must Prove

An internal audit is not a rehearsal for an external assessment. It is your lab verifying, on its own terms, that requirements are met and risks to validity are controlled. Clause intent becomes practical when you translate it into evidence, sampling, and follow-up discipline.

A good internal audit proves four things. First, your system is implemented, not just documented. Second, your technical work is performed according to the current method and within defined controls. Third, your results are traceable and supported by valid uncertainty logic where applicable. Fourth, corrective actions remove causes and do not repeat.

Many labs split audits into “management” and “technical,” but they forget the bridge between them. That bridge is the report. Reports connect contract review, method control, equipment status, competence, calculations, and authorisation. When you audit through the report, you automatically cover what matters.

How To Build A Risk-Based Audit Program

A defensible audit program follows risk, not calendar habit. Risk in a lab is driven by change, complexity, consequence, and history. New methods, new analysts, software changes, equipment failures, complaints, subcontracted steps, and tight customer tolerances all increase risk because they increase the chance of an invalid result.

Keep the risk rating simple so it gets used. A three-tier model is enough. High-risk areas get more frequent audits and deeper techniques like witnessing and recalculation. Medium risk gets a balanced mix of record review and selected witnessing. Low risk still gets coverage, but with lighter sampling and more focus on trend signals.

Independence and competence must be designed together. An auditor who does not understand the technical work will miss the real failure modes. An auditor who audits their own work will rationalise weak controls. Cross-auditing by method families is a practical solution because it maintains objectivity while keeping technical intelligence.

Use the following schedule logic as an internal rule set. This is the fastest way to make your audit program look intentional and defensible.

Set your baseline cycle first, then apply triggers that pull audits forward.

- Cover every method family on a planned cycle, even if the risk is low.

- Trigger a targeted audit within 4 to 8 weeks after any method revision, software update, or equipment replacement.

- Trigger a witness audit for the next 3 jobs after any new analyst authorisation.

- Trigger an audit trail review of the specific report within 10 working days after any complaint.

- Trigger supplier evidence verification each cycle for any subcontracted calibration or test step.

- Trigger an impartiality check when commercial pressure, rush requests, or conflicts appear.

Once these rules exist, keep a one-page record that links each rule to risk and validity. That single page becomes your “why” when someone questions frequency.

ISO 17025 Internal Audit Planning That Tests Results

ISO 17025 Internal Audit wins or loses on one choice. You must select the audit anchor. The best anchor is a completed report because it is the product the customer trusts. Start from the report, trace backward into records and controls, then trace forward into review and release evidence.

Sampling must also be defensible. Avoid “audit everything” because it creates shallow checking. Avoid “audit one record” because it can miss systematic issues. A practical approach is to sample by risk tier, then ensure every critical method family gets at least one full audit trail per cycle.

Clause 8.8 Checklist Table

| Requirement | Audit Question | Evidence Required (IDs) | Y / N / N/A | Risk If Broken (Validity Impact) |

| 8.8.1a | Do we have an internal audit program covering the management system and technical work? | Audit Program ID, Audit Plan #, Scope Map / Method List | – | Coverage gaps hide invalid results |

| 8.8.1b | Is audit frequency based on importance, changes, and past results? | Risk Register ID, Change Log IDs, Last Audit Report #, Schedule Rev | – | High-risk changes go unaudited |

| 8.8.2a | Are audit criteria and scope defined for this audit? | Audit Plan #, Criteria / Clause Map, Scope Statement | – | Audit becomes subjective and shallow |

| 8.8.2b | Are auditors objective and impartial for this scope? | Auditor Assignment Log, Independence Check / Conflict Record | – | Bias lets failures repeat |

| 8.8.2c | Are results reported to relevant management? | Audit Report #, Distribution Record, Management Review / Minutes ID | – | Actions stall, issues persist |

| 8.8.2d | Are corrections and corrective actions implemented without undue delay? | CAPA IDs, Due Dates, Containment Record IDs, Closure Evidence IDs | – | Invalid output may reach customers |

| 8.8.2e | Is corrective action effectiveness verified? | Effectiveness Check ID, Follow-up Audit Plan #, Post-fix Sample Check IDs | – | Same nonconformity returns |

Choose audit techniques that match the risk. A record review is good for document control and contract review. Observation is essential for environmental controls and method adherence. Recalculation is essential for spreadsheets, rounding, and uncertainty logic. Witnessing is essential when competence and technique matter.

Internal Audit Coverage Map for ISO 17025 Labs

Use this matrix to keep coverage balanced and to stop audits from becoming opinion-based. It tells the auditor what to verify and what “good evidence” should look like.

| Lab Process | How To Audit | Minimum Sample Rule | What Good Evidence Looks Like |

| Contract Review | Record Review + Interview | 3 jobs per month | Requirements captured, scope accepted, deviations approved |

| Method Control | Record Review | 2 methods per cycle | Current revision in use, controlled change history |

| Personnel Authorisation | Record Review + Interview | 2 staff per cycle | Training, supervised practice, and authorisation sign off |

| Equipment Status | Record Review | 5 instruments per cycle | Calibration valid at use date, intermediate checks logged |

| Traceability | Record Review | 3 jobs per cycle | Reference standards valid, ranges appropriate, fit for purpose |

| Environmental Control | Observation + Record Review | 2 days sampled | Logs within limits, alarms addressed, actions recorded |

| Calculations | Recalc + File Review | 1 critical point per job | Formula correct, units correct, version controlled |

| Uncertainty Evaluation | Record Review + Recalc | 1 method per cycle | Components justified, budgets current, changes reviewed |

| Data Integrity | System Review + Record Sample | 5 records per cycle | Access control, audit trails, backups, and change logs |

| Reporting And Review | Record Review | 3 reports per month | Independent review evidence, authorised release, controlled template |

How To Run The Audit On The Floor

Execution is where audits become either useful or political. You reduce friction by being precise. State scope, timeboxes, and evidence rules in the opening meeting. Confirm what will be witnessed and what records will be sampled. Make it clear you are auditing process control, not judging individuals.

Evidence notes must be written so that another auditor can replay them later. That means you record job IDs, record IDs, dates, instrument IDs, method revision, and what was observed. Avoid vague phrases like “seems ok.” Replace them with specific evidence anchors.

Witnessing should be selective and purposeful. Watch steps where technique affects outcome, such as setup, stabilisation, intermediate checks, environmental control, and decision rules. When you witness, you are looking for hidden variability, not just whether someone can follow a script.

The One-Report Backtrace Method

This is the fastest way to audit technical competence without auditing the entire lab. Pick one released report and validate its full evidence trail.

1. Start With The Report

Confirm identification, scope, method reference, and authorisation.

2. Pick One High-Risk Point

Select one high-risk point and redo the math from raw readings.

3. Validate Calculation Discipline

Confirm units, rounding, and that the calculation file is controlled.

4. Verify Instrument Status

Verify the instrument used was within calibration on the measurement date, and that intermediate checks exist where required.

5. Check Reference Standards Fit

Confirm reference standards were appropriate for the range and capability.

6. Confirm Environmental Compliance

Verify environmental logs support the method requirements during the run.

7. Verify Analyst Authorisation

Confirm the analyst had authorisation for that method revision at that time.

8. Close With Release Controls

Finish by checking review evidence and template control at release.

This single trail catches the most common failure mode in labs. Numbers can be correct while traceability or control is broken. A technical audit must test both.

How To Write Findings And Close CAPA

Findings must be written like engineering statements. A strong finding ties a requirement to a condition and supports it with objective evidence. It then states the risk to the validity or compliance and defines the scope. That structure prevents debate because it is built on facts.

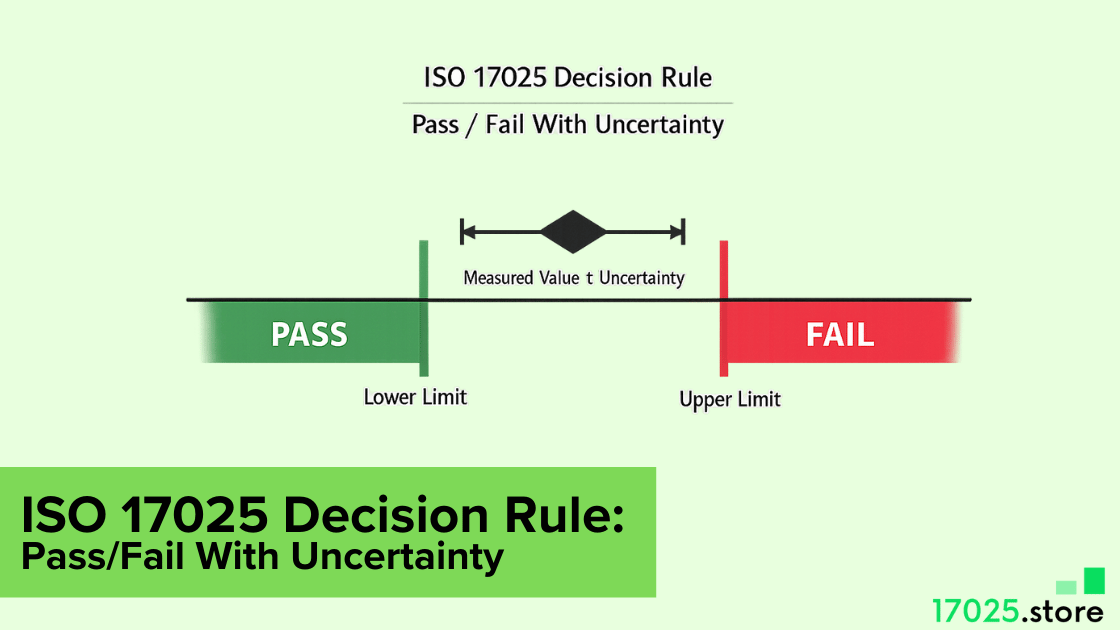

Severity should follow risk to valid results. Anything that can affect traceability, uncertainty validity, data integrity, or impartiality should be treated as a higher priority because it can change customer decisions. Administrative misses still matter, but they rarely carry the same technical risk.

Corrective action should remove the cause, not just patch the symptoms. Training alone is rarely a complete action unless you also fix the control that allowed the error. Spreadsheet version control, template locking, review gates, authorisation rules, and intermediate checks are examples of controls that prevent recurrence.

Use the closure gates below to keep CAPA disciplined and measurable. Apply these closure gates before you mark any action complete.

- Evidence exists. Record IDs, logs, or controlled files prove the fix is real.

- Scope is checked. Similar jobs are sampled to confirm it was not systemic.

- Recurrence control is added. A procedure, template, or gate is updated to prevent repetition.

- Competence is verified. The analyst demonstrates the corrected step under observation.

- Result protection is confirmed. If validity is at risk, affected results are assessed and handled.

- Effectiveness is proven. A follow-up check after 4 to 8 weeks shows the issue cannot recur.

When you use these gates, repeat findings drop, closure time improves, and internal audits stop feeling like paperwork.

FAQ

What Is An ISO 17025 Internal Audit?

It is a planned and recorded check performed by your lab to confirm requirements are met, and results remain valid. Strong audits trace one released report back to raw data, method control, equipment status, and authorisation, then confirm review and release controls.

How Often Should Internal Audits Be Done In ISO 17025?

Frequency should follow risk. Stable methods can run on a planned cycle, while complaints, changes, new staff, new equipment, or method revisions should trigger targeted audits sooner. A defendable schedule is based on change and impact on validity.

Who Can Conduct An Internal Audit In An ISO 17025 Lab?

Auditors must be competent in what they audit and objective in judgment. They should not audit their own work or decisions. Cross-auditing across sections is a practical pattern because it keeps independence while preserving technical understanding.

What Is The difference between a Technical Audit and a Management System Audit?

A management system audit checks system controls like document control, contract review, complaints, and corrective action flow. A technical audit checks method control, traceability, calculations, uncertainty, witnessing of work, and data integrity to confirm that the result pipeline is valid.

How Do You Write A Nonconformity In An ISO 17025 Audit?

Write the requirement, observed condition, objective evidence, risk to validity, and scope. Use record IDs, dates, instrument IDs, and the exact control that failed. Avoid vague wording and avoid personal tone so corrective action becomes precise and testable.

Conclusion

ISO 17025 internal audits are valuable only when they protect the validity of the results. Build a risk-based program that pulls audits forward when changes and complaints appear.

Anchor technical audits to one released report and trace it through calculations, raw data, method control, traceability, environmental evidence, competence, and authorised release. Write findings with evidence and risk, then close CAPA with measurable gates that prove effectiveness. Run audits this way, and you do not just stay compliant. You build a lab that produces defensible results under pressure.